- Home

- John Danalis

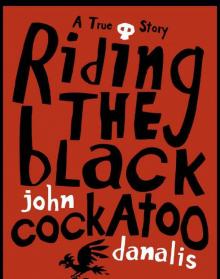

Riding the Black Cockatoo

Riding the Black Cockatoo Read online

Half the royalties from the sale of this book will go to the Wamba Wamba people, and will be used for cultural and environmental projects including the regeneration of Black Cockatoo habitat in the hope that the clan’s totem animal can be successfully reintroduced to Wamba Wamba Country.

First published in 2009

Copyright © John Danalis 2009

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. The Australian Copyright Act 1968 (the Act) allows a maximum of one chapter or ten per cent of this book, whichever is the greater, to be photocopied by any educational institution for its educational purposes provided that the educational institution (or body that administers it) has given a remuneration notice to Copyright Agency Limited (CAL) under the Act.

Allen & Unwin

83 Alexander St

Crows Nest NSW 2065

Australia

Phone: (61 2) 8425 0100

Fax: (61 2) 9906 2218

Email: [email protected]

Web: www.allenandunwin.com

National Library of Australia

Cataloguing-in-Publication entry:

Author: Danalis, John.

Title: Riding the black cockatoo / John Danalis.

ISBN: 978 174175 377 6 (pbk.)

Subjects: Danalis, John.

Danalis family.

Wamba Wamba (Australian people).

Aboriginal Australians – New South Wales – Riverina – History.

Aboriginal Australians – Antiquities – Collection and preservation.

Restorative justice.

Human remains (Archaeology) – Repatriation – Australia.

Dewey Number: 305.8815

Cover and text design by Stella and John Danalis / Peripheral Vision

Set in 11.5/18 pt Adobe Garamond Pro by Ruth Grüner

Printed in Australia by McPherson’s Printing Group

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

This project has been assisted by the Australian Government through the Australia Council for the Arts, its arts funding and advisory body.

To my mother and father,

who said Yes'

To Bianca and Ebony,

our future

Acknowledgements

Many hands carried Mary back to Country; your names, tears and smiles are woven into these pages.

Writing this book has also been a part of Mary’s homecoming.

I humbly give my thanks to those who listened when I needed to speak (sometimes about the unspeakable), and encouraged me to stay at the keyboard (even when it seemed like the most inhospitable place on the continent): Judy Saunders, Boori Monty Pryor, Dr Max Quanchi, Bryan Cook, Matt Cassidy, Steve Wyborn, Peter Creagh, Alan Hamilton, Helen Belle Bnads, Dr Pee Tek Chan, Stella Danalis, Ruth Grüner, Erica Wagner, Sarah Brenan.

WELCOME TO

COUNTRY

Kurrumeruk the giant Murray cod, chased by the Yemurraki Dreamtime Rainbow Serpent, made the rivers, lakes and billabongs. Their tracks like our Ancestors are everywhere in Wamba Wamba Country. Burials form part of the tracks on our journeys to the afterlife.

Reconciliation means balancing the book of history. It is also about balancing out the injustices of our past with justice for the future so we can be at peace with our families, other people and the environment we live in. We take the good, the bad, ugly and beautiful in our histories. One ugly stain in shared history can become a glorious but profound point in our journey. Wiran, the black cockatoo with red feathers, has taken us for a flight of beauty and wonderment returning our lost Ancestor to Country.

Our Esteemed Ancestor has been returned by Warriors of a different ilk, but strong in common purpose. Strong people with strong minds know what is right and what is truth. Kindness and truth will open doors and break down barriers. Rivers of tears and a blue sky filled with weyi (song), warrang-warrang (corroboree) and joy, such is the wonder of the flight with the Wiran back to the yemin-yemin (burial ground) of the Wamba Wamba. Welcome to Country.

{ WYRKER MILLOO GARY MURRAY

WAMBA WAMBA NATION, MURRAY RIVER

APRIL 2009 }

FOREWORD

‘Just a whitefella who’s learned to listen, that’s all,’ says a Wik woman about John Danalis. Through listening comes this story about a skull called Mary, going home.

Some of it hurts. ‘Like a kangaroo – iconic in the wild but troublesome in our paddock’ is a reflection of me through the eyes of others. It puts a hurting on my heart so bad it makes the thought of death welcome. This is but one of the many ugly reflections in this amazing story that need to be read quietly inside then said out loud for all to hear.

But then there’s the proud-to-be-a-blackfella words, ‘You tell your old man how much the Wamba Wamba nation appreciates what he’s doing. Tell him I’d like to buy him a beer. We really owe you for this one. We owe you big time.’ Those words made the happy tears flow and mingle with the sad ones to make a pool of healing kilta (salt water) for my heart to swim in.

Selfless in its search for sanity of the soul, majestic and poetic, Riding The Black Cockatoo is a nation’s journey through its growing pains of race and colour. We lie within the pages of black on white. We belong to this story and it belongs to us. Thank you, John, for having the courage to search and find ways that will make us all better. Waddamullie wadjabimbi. Thank you, welcome.

{ BOORI MONTY PRYOR

CO-AUTHOR OF MAYBE TOMORROW

MELBOURNE, MARCH 2009 }

THE DOOR THAT

SHUTS YOU OUT

IS THE SAME DOOR

THAT LETS YOU IN

{ OLD INDIAN SAYING }

CONTENTS

CHAPTER ONE

CHAPTER TWO

CHAPTER THREE

CHAPTER FOUR

CHAPTER FIVE

CHAPTER SIX

CHAPTER SEVEN

CHAPTER EIGHT

CHAPTER NINE

CHAPTER TEN

CHAPTER ELEVEN

CHAPTER TWELVE

CHAPTER THIRTEEN

CHAPTER FOURTEEN

CHAPTER FIFTEEN

CHAPTER SIXTEEN

CHAPTER SEVENTEEN

AFTERWORD

CHAPTER

ONE

Have you ever blurted something out in conversation, and a nanosecond later wished that you’d kept your trap shut? Well, that’s the way my family secret came out – blurt ! And once my secret was out, it just sat for all to see, like a bright blue jellyfish washed up by a king tide, stranded between the double glare of sun and sand, wishing it could wobble back into the ocean and glide inconspicuously once more among a billion other jellyfish secrets.

{ BRISBANE, LATE AUGUST–EARLY NOVEMBER 2005 }

This story goes way back, further back than any of us can imagine. But it became part of my family’s dreaming just before I was born, 40 years ago. Like a distant storm flickering across the horizon, this story crept across the landscape patiently; it knew just when to announce itself, just when to hit. And when this story first began to rattle my windows I was a man – or perhaps just a boy – lost, still trying to find my path.

I’d tried lots of things in life, but nothing had stuck. I still hadn’t found what I was meant to do, what I was supposed to be. I had a wife now, and two daughters who seemed to be blowing out birthday candles every other Sunday. I felt time was ebbing away. So I enrolled at university as a mature-age student and began a double degree in arts and education; I was – to everyone’s great relief – soon to become a teacher. And it was th

ere that I enrolled in a class called ‘Indigenous Writing’. This class was a departure from the other subjects I’d been studying. I’d signed up for Indigenous Studies units in previous semesters but always chickened out at the last minute and changed to something ‘safer’. I was unsettled by so many things surrounding Aboriginal Australia; I felt ashamed of my own ignorance of their culture, I felt guilty and dirty over our theft of their country, and deep down, perhaps I was afraid that they possessed ‘something’ that if unleashed might upset the nice orderly nature of my white world. But I knew that I had to learn about Aboriginal culture and history – after all, I was studying to become a teacher, and an understanding of Australia’s traditional owners seemed to me as important as anything I might teach in maths or science. So Indigenous Writing seemed a soft way in, and besides, the unit covered indigenous writing from all over the world, so it wouldn’t be too confronting, too uncomfortable, too Aboriginal.

It was a small class of about fifteen, and the discussions meandered all over the place like a long, winding creek. Our lecturer was one of the sharpest people I had ever met, and the reading list she prepared read like the itinerary from an adventure holiday company: Inuit short stories, nineteenth-century anti-colonial novellas, Native American chants, desert poetry. It was like sliding into a warm bath with a stack of National Geographics close at hand. Each week we got together for three hours to discuss the readings, setting off like well-fed, middle-class adventurers into the literary landscapes of ‘the Other’. What a strange term, ‘the Other’; to white people it conjures up images of figures lurking in the shadows, of big round eyes peeping out from the jungle edge, and in a strange way that is exactly what it refers to – people living outside the mainstream. Yet the term was originally coined by persons of colour (particularly coloured women) as a way of discussing the cultural dominance of mainstream society and the methods used to mark them as inferior. Over time the term has been embraced by other groups whose genetics, sexual orientation and lifestyles defy convention; the sort of people who baffle, shock, antagonise or titillate ‘straight’ society. But most commonly the term is still used by Indigenous people as a way of understanding how ‘Otherness’ has been forced upon them. ‘The Other’; it was a buzz-phrase our little group deployed with uncomfortable regularity – as if any of us could ever truly understand what it meant to be shoved to the margins of society. We were all white, and most of us had similar world views; it was a caricature of a liberal arts class, in a safe, cosy environment. Of course, what the class really needed was half a dozen Indigenous people – or even one. Now that would have taken the discussions into some interesting territory! Besides our worldly lecturer, I don’t think many of us in the room knew – really knew – a person of colour. In this class, the closest we came to ‘the Other’ was the occasional visit from an extremely angry young woman who felt the need to remind us regularly that she was ‘queer’ as well as thoroughly pissed off with the world. A heavy vapour trail of marijuana followed her into class and everywhere else she went on campus. But she seemed just as much of a cliché as we were. We all had the luxury to buy into whichever off-the-rack look we felt best projected our self-image: tree-hugger, tree-cutter, flag-waver, flag-burner – we all had the opportunity to choose. Cocooned in the cottonwool of white-bread suburbia, we were all quite comfortable and, I suspect, quite numb.

{ 14 SEPTEMBER 2005 }

After many weeks of sampling the outer reaches of Indigenous literature, the class finally got around to discussing ‘the Australian situation’. We were sitting, as usual, around a long table sipping tea and coffee. It was very informal and relaxed, a class reminiscent of the ‘good old days’ when universities were places of inquiry and exploration rather than the biscuit-cutter conveyor belts of vocational training they tend to be now. I had scurried in late, but not very late; being a mature-age student I was generally punctual and studious (I’d been ejected from two campuses some 20 wild years ago and was determined not to blow it this time). As I took a seat, my ears pricked up; our lecturer was halfway through a confessional about her family’s dark past. She recounted the brutal divide between the whites and Indigenous peoples of her childhood town in northern New South Wales. Aborigines fulfilling community service duties, usually as punishment for minor offences, were allotted the most humiliating and disgusting tasks by the community’s police and menfolk. Often they were forced to work naked, sometimes before jeering onlookers with cameras. As she began to revisit the degradations and humiliations that these men and women had been subjected to, our lecturer’s voice tapered off into an embarrassed silence, as if she’d already said too much, as if she’d already betrayed her bloodline. But she didn’t need to go into detail; the weight that clawed at her face and shoulders finished the story and hinted at an upbringing burdened by unresolved memories. She would later share with me that she had kept closeted away, safe from her father’s bigoted gaze, a photograph of her childhood tennis idol Evonne Goolagong.

Then came my announcement. Perhaps I said it to divert some of the attention away from the rattlings of my lecturer’s family skeletons; I also suspect I said it partly out of the desire to go one better – mature-age students can be terrible know-alls and I was no exception.

‘Well; I grew up with an Aboriginal skull on my mantelpiece.’

I said the words with a sort of worldly swagger, somehow expecting the announcement to impress my younger classmates. I might as well have unzipped my pants and flopped my penis onto the table – everyone turned and stared at me with a mixture of incredulousness, disgust and horror. My worldliness withered. There was silence; and in that seven-second eternity my childhood was teleported from the Polaroid feel-good fuzziness of the 1970s into the cold, hard glare of the year 2005.

And then came the chorus. ‘You what ? You have a what in your living room?’

‘No, no, not my living room,’ I backpedalled furiously; of course I was too enlightened to permit such a heinous display in my own home. ‘It was on my family’s mantelpiece, in the family home, where I grew up, and it’s not as bad as you think, things were different back then . . .’

Now it was time for my voice to taper off. A different kind of silence filled the room. It was a silence accompanied by a collective unblinking stare, and I sat at its epicentre.

‘Some—’ my voice squeaked, ‘someone – an uncle, actually – gave it to my father when I was a baby. I grew up with it, it was always there. Dad collected stuff, it just sat up on the wall unit with all his other bits and pieces; old stuff, rifles, wild boar tusks, deer antlers—’

The eyes grew wider.

‘Guns?’ asked one girl, almost tearfully. ‘You mean this Aboriginal skull is displayed with guns, like a trophy?’

‘And pigs’ tusks?’ added another.

‘Country people, my family are country people, we grew up with guns. And it’s not what it sounds like. Dad’s a veterinarian, he’s into stuff like that, he’s even got two Siamese piglets floating preserved in a fish tank full of formaldehyde. The skull was a scientific curio, not a trophy.’

But it was too late; I had waded so far out into the gloop that every word I uttered just mired me deeper. I was up to my bottom lip in it. My beloved childhood home sounded like a cross between Ripley’s Believe It Or Not and the trophy cave from Wolf Creek.

‘Is it still there now?’ asked the teary-eyed girl.

‘No-o-o,’ I answered with unconvincing reassurance. ‘I asked Mum to put it away years ago, when she started babysitting my daughters. I didn’t want them spooked out.’

‘Spooked out’; what an understatement! Eventually the eyes turned away and the discussion moved on. And there I sat, utterly deflated. Over the years I could have filled a hot-air balloon with my bluster about equality, justice and the brotherhood of man; but here was this terrible truth – this secret shard – that brought my seemingly normal childhood and world view crashing back to terra firma.

I can’t reca

ll the first time I saw – I mean, consciously recognised – an Aboriginal person. Children, after all, don’t naturally differentiate between people of colour, it is adults who hand out the labels, generation after generation. ‘Australian Aborigine’ sounds so anthropological, almost zoological – like ‘Australian marsupial’. Yet in a strange way that was how I was brought up to see Indigenous Australians, as some sort of museum exhibit; an oddity that sat somewhere on the evolutionary scale between Og the Caveman and a brave white fellow in a pith helmet called Rupert. I was taught that it was acceptable to marvel at the Aborigine in his natural setting – preferably in the most distant corner of a far-flung desert, where he could launch boomerangs or sit in the shade of a brigalow tree to his heart’s content. We admired his hardiness and his healthy, gleaming, ‘Yes, boss’ smile as he looked up to the camera – as long as he stayed on the far side of the horizon. Like the kangaroo – iconic in the wild but troublesome in our paddock – Aboriginal contact tended to upset our idea of the order of things. Indigenous people disturbed the neat fencelines of our logic; they messed with our empirical minds. For their collective mind seemed like a mysterious storehouse stacked high with what the modern world considered superstitious mumbo-jumbo and redundant knowledge. Only now are we awakening to an understanding that this 60 000-year-old storehouse holds answers to questions we have just begun to ask. The custodians of this storehouse possessed a playful ability to live in the moment that both baffled and annoyed the hell out of us. But of course our biggest bugbear was the colour of their skin.

Black. The negative images embedded in our language go back centuries; black is the night, black is my soul, burnt black, eyes black with rage, black heart. To a white boy growing up in the safe, suburban 1970s, ‘black’ conjured up the beating native war drums of Saturday-afternoon Tarzan movies. It meant cannibal cooking pots, violated white missionary women, and spears thrust deep into the unsuspecting backs of noble explorers. It meant voodoo, shrunken heads, witchdoctors and inexhaustible armies of fanatical Zulu warriors. As a small child I was chased down the jungle tracks of my imagination by every black cliché imaginable; a Negroid Frankenstein stitched together from Hollywood and Boy’s Own Annuals. African, Caribbean, Islander, Australian; they were all tarred with the same evil brush. Black was black, and even in a suit or a doctor’s gown, I was warned, a spear-chucker lurked just below the surface. As I type these recollections I cringe at how monstrously offensive such stereotypes are. In fact, I can’t believe I’m writing this at all. Part of me wants to skip to the next chapter; it would be so much easier for all of us. But if this story is going to make any sense, it has to include everything; I need you, my reader, to peek into the freight cars full of baggage I’ve been dragging behind me all these years. Of course, none of this will be big news to Indigenous folk!

Riding the Black Cockatoo

Riding the Black Cockatoo