- Home

- John Danalis

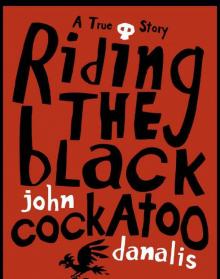

Riding the Black Cockatoo Page 3

Riding the Black Cockatoo Read online

Page 3

No episode of Skippy was complete without nailbiting drama, and halfway into the show it came from the sky. On a routine air patrol over the park, Jerry decided to look for Sonny in the Hidden Valley. As the helicopter blades thrashed at the air over Tara’s campsite, the terrified elder became convinced that the horrendous hovering noisemaker was the ‘spirit of death’. Tara ordered his young friend to leave the valley so that he could prepare to join his ancestors. ‘Time for Tara to die, leave this place of death.’

‘Please, Tara, please don’t die. We’re not going to let you die,’ Sonny pleaded, tears streaming down his freckled cheeks.

That afternoon, little kids all around Australia repeated Sonny’s words like a mantra: ‘Please, Tara, please don’t die!’

And then, something truly terrible happened. Three little words crawled across the screen: ‘To be continued . . .’

The Tara episode was just too big to fit neatly into a half-hour slot, and had been split into two halves. The words To be continued could be a devastating thing for a child of seven. That evening as I slurped milk from my Skippy mug and picked listlessly at the dinner on my Skippy plate, I stared blankly into the lime-green geometric kitchen wallpaper, pondering Tara’s fate. As I lay in bed under the subtropical sky, my sweaty head tossed and turned on my Skippy pillowcase. The next day, there was a palpable sense of tension in the schoolyard. By four o’clock, the streets, playgrounds and back yards that usually resonated to the sounds of bicycle bells and cricket bat thwacks fell silent. Every little Australian knew that in Aboriginal culture ‘pointing the bone’ was an act of sorcery, a curse that brought about certain death. I’m sure my little brother wasn’t the only bullied child to point a half-gnawed chop bone at an annoying older sibling and announce, ‘That’s it, you’re dead.’ But this was the real deal; Tara had effectively pointed the bone at himself and was halfway back to the Dreamtime. Only Sonny and Skippy could save him. It was absolutely gripping stuff, and we were all as gripped as gripped could be!

As the sun slowly set on Tara’s life, Sonny desperately rummaged through the old man’s few belongings and discovered a medal and citation for bravery. As a younger man, Tara had heroically saved a small boy from drowning, and that small boy had grown up to become a powerful dignitary. Upon hearing of Tara’s plight, the well-heeled dignitary organised the airlift of a songman and a full troupe of dancers from Tara’s far-flung Akara tribe to be by their fading tribesman’s side. Skippy the Bush Kangaroo had never seen anything like it, and neither had we; a dozen painted-up full-blood Aborigines (in underpants) dancing in jerky supernatural movements. The continual drone of the didgeridoo and the clack-clack of clapsticks echoed throughout the Hidden Valley and through Australian lounge rooms from coast to coast. The ceremony ran uninterrupted for ten mesmerising minutes. The dancers jerked slowly around an unconscious Tara, tension building, until at last his eyes flickered open and he slowly rose, joining his tribesmen in their otherworldly dance. And so the ending was a happy one; Tara was saved and allowed to stay on in the park, and Australian children were treated to an extended encounter – however artificial – with Indigenous Australia. At the end of the show, after some well-intentioned dialogue about black and white having much to learn from each other, Tara pronounced that ‘Tara has many friends.’

I’m sure that at that moment every child watching wanted a friend just like Tara; a friend to reveal to them the mysterious secrets of the country in which they lived. For most of us, however, there would be no Tara to show us the ropes, and besides, we would soon be too distracted growing up into busy white Australians to remember or care.

I returned from my memories, rose and opened the centre TV cupboard of the wall unit again. Inside, stacked high, were videotape towers of AFL football games – Essendon games mostly, and a smattering of finals matches. I poked my head into the cupboard for a closer look. As my nostrils registered the faint, lingering whiff of burnt-out Rank Arena valves, I accidentally brought down a teetering pile of videos. There he was, Mary, upside-down in the far back corner of the TV cupboard – how uncomfortable he looked. Gently taking the skull from the cupboard, I returned to my father’s chair. I put him to my nose and inhaled (don’t be shocked, we were old friends). My grown-up fingers reconnected with him, tracing the little cracks that ran like the rivers of a faded atlas. The temple – the area known in spirituality as the third eye – was corroded by the syphilis that would have gnawed away at Mary’s sanity and spirit.

Placing two fingers into the base of the skull, I recalled how once my entire hand and wrist could fit inside this space; I remembered the way I once wiggled my index and pinkie fingers through the eye sockets like graveyard worms. My fingers glided over the dry interior; once there was fluid here, and a brain floating in a continuous synaptic lightning storm that swept this way and that over a landscape of consciousness. Hunger and contentment, triumph and disappointment, wonder and awareness, every thought and feeling; they had all resided there in that cavity. My fingers felt like a stranger’s legs, tiptoeing about in a long-deserted house, wondering at the private dramas and dreams which had once played out inside.

How yellow it had gone. Dad used to lacquer the skull every so often to prevent the bone from crumbling away into chalk and, I suspect, because he enjoyed lacquering things. After Mary was given to him, he had glued the lower jaw into position with Araldite and fixed a matchbox-sized block of wood to the base of the skull to prevent it from tipping over backwards. The teeth – except for one at the front – were all accounted for and in remarkably good condition – testimony, no doubt, to a cola- and chip-free diet. There had been the odd occasion in the 40 years that Mary sat on the shelf, firm-jawed and resolute, when some joker – usually when my parents were hosting a party – had placed a cigarette into the gap left by the missing tooth. And there were a few occasions when my younger brother Guy and I would test the nerves of the neighbourhood kids by placing a small pocket torch inside Mary so that the eye cavities and the slight gaps between his teeth glowed with an otherworldly radiance. We had the ultimate jack-o’-lantern. Although we sometimes revelled in the macabre weirdness of living with a skull on the mantelpiece, we always handled Mary with care. Apart from the occasional cigarette, Mary was never mocked or ridiculed; he became part of our landscape. It seemed no different to having my grandmother’s ashes on display next to my grandfather’s false teeth and a dried-up block of his favourite chewing tobacco (which we did!). There was a twisted yet sweet form of suburban ancestor worship going on in our house, and in a weird way Mary had come along for the ride.

My rational self knew the skull was as empty as the abandoned shell of a hermit crab, yet my heart told me otherwise; I felt something, but whatever it was, the harder I tried to see it – to understand it – the further I pushed it away; it was as elusive as mist. I tried to send some positive thoughts to the bones in my lap, something profound, but it was a strain to think; I wondered if I was losing my mind, yet at the same time there was a rare and unfamiliar calmness about my thoughts suggesting I ride this ripple that seemed to swell with each passing moment. I put Mary back with the tapes – the right way up this time – and jiggled him about a little to make him more comfortable. Then the words came, three simple words: ‘You’re going home.’

CHAPTER

THREE

{ 19 SEPTEMBER 2005 }

Missed my morning lecture, again. Interpersonal Relationships 101, not exactly the most captivating of subjects, but it would take me twelve credit points closer to a degree I should have finished years ago. And besides, I’d decided that some of my own interpersonal relationship skills could do with a bit of an overhaul. In a sunny corner of the library I scanned the weekend papers before attempting the set readings from my textbook. Mary was never far from my thoughts and there was a notion forming in the back of my brain that perhaps I could approach the University for help.

At lunchtime, I spied Craig from the Oodgeroo Unit (the campus

Indigenous education and support department). He was eating lunch, alone.

‘Do it, man, just walk over there and do it,’ I told myself.

Craig had been a guest lecturer last semester in one of my Community Studies units, so I felt as though I knew him a little. He had opened his lecture with a simple yet powerful little ‘party trick’; he fished all the loose change from his pocket and laid the coins out in a neat line on the overhead projector, from the lowest denomination to the highest.

‘Five-cent piece – the echidna,’ he began. ‘Ten-cent piece – the lyrebird; twenty-cent piece – the platypus; one-dollar coin – a mob of kangaroos; two-dollar coin – a blackfella.’

He paused for a moment, waiting for the penny to drop; it hadn’t yet for me.

‘That fella there is supposed to represent Indigenous Australia,’ he said, pointing to the chiselled face of the black bushman on the coin. It was the sort of iconic cliché that is part of the Australian lexicon; an Aborigine frozen for a moment as he stares out from some faraway escarpment at his vanishing country. It’s the same blackfella who appears on old prints, postcards and biscuit tins; he balances on one sinewy leg, leaning ever so slightly on a brace of spears. It’s an image that acknowledges a certain wisdom and grace, yet has a loneliness about it suggesting this fellow – like Tara – is the last of his tribe.

‘And look at this, here’s an extra little insult.’ He pointed the tip of his pen to a grasstree cast into the background of the coin. ‘You know what those are called, don’t you?’

Half the students in the lecture theatre mouthed the word ‘Blackboy’.

Craig nodded. He looked pleased that he’d made his point, yet there was a hint of weary bitterness simmering just below.

‘You see, this is where we fit into the white scheme of things, as fauna, part of the animal kingdom, part of the landscape.’

One brave soul raised his hand and reminded the lecturer that the fifty-cent piece could have any number of things on it, like Captain Cook, or Charles and Diana. Craig laughed as if he’d expected the comment, ‘Ah, the fifty-cent piece, that’s the wild card, it can have anything on it, but it’s usually a famous whitefella.’

Then he asked, ‘How would you like to see a generic white person on that coin? Can you imagine where you would even start? You’re all so different, you’ve all got different stories. Well, it’s the same with us.’

Now I wandered across the grey expanse of concrete to where Craig sat outside the bustling University refectory. I asked if I could join him. He looked up, a little surprised, not sure if he should recognise me or not.

‘Sure,’ he answered, ‘but I’m heading back to the office in a sec.’

As I explained that I needed to talk to him about ‘something sensitive’, I realised that this was the very first Indigenous Australian I’d ever spoken to one-on-one. Then without missing a beat I announced that my family had had one of his kin on display in the family lounge room for 40 years. I might as well have just walked up to the man and punched him in the guts. He recoiled in his seat as pain and disbelief tore across his face. Again, the seconds groaned – taut, dislocated from the clock time that marched on about us. Craig recovered, pushed away the last remnants of his sweet-and-sour pork, and rose to his feet.

‘You’d better come with me,’ he said; there was just the hint of an order in his tone. Not a word was exchanged as he led me to the Oodgeroo Unit, named after the famous Aboriginal poet and activist Oodgeroo Noonuccal.

As we entered the office I immediately felt like an outsider, a whitefella in a blackfella place. It wasn’t threatening, but the very atmosphere felt different. If you have ever visited a foreign consular office you’ll know the feeling I’m trying to describe, it’s as if a tiny piece of one country has been transplanted into another, and that’s what this was like, a portal into Indigenous Australia. Black faces looked down from posters, and dot paintings, flags and panoramic photographs of wild Australia adorned the walls; there was familiarity about much of what I saw, yet at the same time everything was imbued with a different meaning. It was as if I’d stumbled into a parallel universe and now I was the foreigner!

Craig led me through to his office. A poster of the boxer and football star Anthony Mundine glared at me as though he was about to jump from the photograph and jab my soft white nose repeatedly! I stiffened for a moment, and then understood how this fighter, whom I’d always dismissed as an angry egomaniac with a super-sized chip on his shoulder, could be an inspiration to many of his people. Why had I looked down so disapprovingly upon black anger? Why was it acceptable for whites to get angry, but not black people? I looked around the room for a softer visual to grab hold of and my eyes settled on a photograph of Craig’s wife and kids. There were photos of the land too – beautiful photos of rippling red soil and purple skies, the steamy, still breath of wetlands, and eternally teetering mega-boulders. I breathed easily again, comforted by these things that bind us.

Craig asked me about the skull and I let my story unfold. Every so often I paused and he shook his head rapidly as if to make sure his ears were not playing tricks on him. He looked at me with equal measures of sternness and sadness. ‘It has got to go back, there’s no question about it. You’ll just have to convince your old man to give it up. It has to go back.’

At first I was a bit shocked; I wasn’t exactly expecting a pat on the back, but I hadn’t anticipated such grave (no pun intended!) seriousness either. I’d just presumed that there was some place, some department to send ‘lost skulls’ to and that was the end of the story.

I told Craig that all I knew about Mary’s origins was that he was pulled from earth somewhere outside the Victorian town of Swan Hill. Craig led me outside to the hallway, where a tribal map of Australia was displayed. It was beautiful, a 200-piece patchwork of colours, but the only thing familiar was the map outline. I was staring into a country – or rather a collection of nations – I had never seen before. I looked for the state of Victoria and struggled to find where it started or ended. Each coloured patch blended organically into those around it; there were no neat pieces and no straight lines, the surveyor’s straight edge was totally absent. Craig smiled as I struggled to navigate my way about a country that only a few minutes earlier I’d thought I knew so well – I was lost.

The patchwork pieces were much smaller and more numerous in the fertile floodplains of northern Victoria. Tribal names like Yorta Yorta, Wadi Wadi, and Nari Nari jumped out from beneath Craig’s circling finger. He located Swan Hill, one of the few English placenames printed faintly on the map as a whitefella reference point.

‘Mate,’ Craig said slowly, his finger lightly tapping the tiny spot on the southern banks of the Murray River, ‘if he was dug up outside of Swan Hill, then there’s a good chance he belongs to this mob.’

I had never read or heard of the name before. I said it aloud – ‘Wamba Wamba’ – and in their enunciation the two words would be forever forged into my own family’s dreaming.

As we settled back into Craig’s office a large figure sailed past the doorway.

‘Rob! Got a sec?’ Craig yelled into the wake left by the big man. ‘That’s Rob, he’s the fella we need to speak to.’

A wild head of hair poked around the door. Craig recounted my story, and with each sentence Rob inched into the room like a bear being drawn out of the forest by the promise of honey. When Craig got to the part about the mantelpiece, Rob flinched as if he’d been stung on the nose.

‘Wha-huh, how could anybody do such a thing?’ he asked.

Craig shrugged and shook his head again. ‘Listen, John, it’s nothing personal, you’re doing the right thing, but I just can’t imagine keeping a skull on my mantelpiece. It’s like me ringing up Rob here and saying, “Hey Rob, I’ve got the skull of a dead whitefella on my bookshelf, wanna come over and see?” ’

The two men chuckled, and for the moment I felt a little better.

‘Yeah,’ said Rob, �

�just imagine what the papers would say: “Savage headhunters display white man’s head.” ’

I sat there, wondering how on earth I was going to bring up the subject with my father. I asked for some advice on how to approach him, some arguments that would help back up my case. Craig looked at me as if I had just asked the dumbest question of all time.

‘What justification do you need? It’s not yours. What your family has done is wrong.’ Craig’s tone was firm, but still, there was no animosity in his voice.

‘Okay, okay.’ His voice softened. ‘You could talk about the dignity of the dead – you know, look at how much effort you whitefellas put into finding and bringing home lost servicemen from the various wars. It’s the same thing.’

I nodded. As a paid-up RSL member, Dad would relate to that. Then Rob brought up the subject of curses. You only had to take one look at Rob to know he was a nice bloke with a big heart to match his sizeable frame, but he was clearly unsettled by the very thought that anyone would be foolish enough to keep human bones under their roof.

‘Mate, have you been to Uluru and seen that pile of stones?’

I shook my head. With the wide eyes of someone who clearly believed in bad juju, Rob described the steady stream of packages that arrive at Uluru containing rocks returned by pilfering visitors.

‘Those rocks come back from all corners of the world; there’s a book full of the letters from people detailing the bad luck they have had and begging for forgiveness. The rangers don’t know exactly what part of the park the rocks come from, so they add them to a pile out the back of the visitors’ centre. It’s a big bloody pile, brother!’

He shuddered visibly. ‘If a little pebble from Uluru can bring bad luck, what kind of trouble do you think taking a skull from its country and keeping it in your home is gunna bring you?’

CHAPTER

FOUR

{ 20 SEPTEMBER 2005 }

Riding the Black Cockatoo

Riding the Black Cockatoo