- Home

- John Danalis

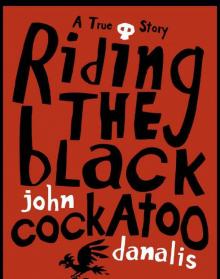

Riding the Black Cockatoo Page 13

Riding the Black Cockatoo Read online

Page 13

‘That’s exactly how I felt when I was there,’ I said, recalling the worn stonework of England, eroded water-like by time’s passing footsteps.

‘Well, I reckon that grindstone would have the same effect on Aboriginal people, especially the young city ones who haven’t spent much time in the bush. After the ceremony I thought about the courtyard, what a peaceful place it was – imagine if that grindstone was set up there with a bit of a plaque, people could go and run their hands over it for years to come, long after we’re gone.’

I agreed with my father, and in my imagination I could see Aboriginal students reconnecting and drawing strength up through their hands; retracing the grooves and furrows of the past and with every infinitesimal finger-stroke adding their own story to this rock of ages. But not just Indigenous fingertips; the open hands of all races could acknowledge the past and add to the songlines within the stone.

‘Listen, son, can you let the University know that I’d like to donate the grindstone? Tell them I’ve got a one-tonne ute, but they’ll need to round up a few strong blokes to lift it, it’s bloody heavy; we had to use a tractor to pull it from the creekbed.’

As far as Dad was concerned it was all sorted – one quick phone call and the grindstone would sit in its new home happily ever after. I was moved by my father’s new-found goodwill and zeal, but at the same time alarm bells were pinging in my ears. Where had the stone come from; who were the rightful owners? Was it a sacred stone to be accessed by males only?

I cleared my throat. ‘Listen, Dad, I love that stone too and I know how much it would mean to you to give it back, but there are all sorts of politics and protocols involved, we’ll have to approach the rightful owners first—’

Dad made one of his bristling grunt sounds, the kind that roughly translated into ‘What a lot of bullshit!’

‘Look, besides all that, I think we’d better cool it for a while, everyone’s just getting over the last handover. Let’s give it few months. If I ring up now they’ll start thinking the Danalis family are a mob of bloody pirates; they’ll be wondering what else you’ve got stashed away under the house!’

Dad burst out laughing. ‘You’re probably right, son, let’s give it a few months. You’ll know when the time is right.’

But my father’s change of heart didn’t end there. A few months later he phoned and asked me if I wanted to go to the movies. Dad is a devotee of the action thriller genre; if it involves galloping horses, nuclear submarines or bent CIA agents, he’s in celluloid heaven. So it came as shock when he invited me to see Ten Canoes, an Aboriginal-language film with all-Aboriginal cast set in Arnhem Land. I’m not sure if I spent more time during those 92 minutes watching Dad or the movie. He sat between my mother and me happily chomping popcorn; gone was the tension I’d sometimes witnessed as a boy when Aboriginal faces – particularly those of activists or demonstrators – would appear on the television screen before him. He was relaxed, comfortable.

I should have followed my father’s example, happily reconciling past and present and just gotten on with life. But I couldn’t stop there, I had to keep scratching, I had to dig deeper. I followed the Wamba Wamba closer to the coming of my own people, closer to my own time, and as I did so my mind began to fall apart.

There had been visitors to Victoria’s shores before – unrecorded seafarers, documented explorers, whalers and sealers – but the effects of the new settlement at Port Phillip reverberated across the Aboriginal world like a cannonball being dropped into a glassy-surfaced billabong. Many clans rode the initial waves, often adapting to and accommodating the visitors as gracious yet curious hosts. But the waves from colonisation and settlement were unrelenting, pushing ever outward. The combined force of the waves equated to a tsunami, and here there were no Blue Mountains to slow its surge, to allow the Indigenous peoples to catch their breath. The clans of south-eastern Australia had unwittingly prepared the land for a rapid European pastoral expansion through centuries of burning and land management. Within a few short years of Victorian settlement in this arcadia, the old men I had ‘witnessed’ in their slender craft were swamped. The parties of family groups making their way to the annual Bogong moth feasts and the annual fishing festival on Lake Albert were swept away. The fires and smoke which presided over eons of ceremonies and knowledge were doused and all but extinguished.

My days became increasingly boxed in by the saddest of books, whose pages carried the anguished cry of a culture dumped on its head. I read accounts of possum-skin cloaks traded for flimsy, perpetually damp blankets, of daughters and wives being traded for rum and tobacco, of a society whose legs were kicked from beneath it by misguided good intention, neglect, treachery and brutality. And it was the brutality that brought me to my knees. Like many Australians, I possessed a vague awareness of the frontier violence that had unrolled across the continent for well over a century after contact. But it was only a few strands of understanding; a whisper carried on the wind that unspeakable things had occurred out there, somewhere to the west, somewhere over the horizon. For 200 years we’ve made too much noise with our busyness for our collective conscience to hear. We’ve all sped past forlorn-looking highway signposts bearing place names like Murdering Creek, Slaughterhouse Gully and Butchers Ridge, but the meanings of these placenames barely register as we hurtle towards tomorrow at 120 kilometres an hour. And when we are occasionally confronted with the past we brush it off, believing that the violence was sporadic, short-lived and sadly inevitable. But too often, it was anything but that.

I read book after bloody book. I read of officially sanctioned vigilante parties whose members’ rifle butts were proudly notched with kills from campaigns of blind and prolonged retribution. I read of craven individuals like the shepherd who tricked visiting natives into eating plaster of Paris instead of flour, and the squatter who enjoyed giving shaving demonstrations to local tribesmen using the upturned skull of one of their clan as a shaving bowl. For a while I rationalised that these were brutal times and that acts of savagery were perpetrated by both black and white. But as I waded deeper into the pages detailing the rapes, poisonings, shootings, bludgeonings and full-scale massacres, it became painfully obvious that the undeclared frontier war was a one-sided affair. And unlike traditional wars with rules of engagement and codes of conduct, here the Europeans often acted with very little honour or restraint – in fact, many of the ‘engagements’ were little more than human culls.

I began to wonder if I was the only whitefella in my neat little suburb who was privy to our nation’s dirty secret. I bailed up friends and neighbours. Of course most people knew something – and lots of people knew far more than I did – only they didn’t relish me standing centimetres from their faces asking, ‘Do you know what we’ve done, do you know what we’ve done?’ like the Colonel Kurtz character from Apocalypse Now. I quickly discovered that the fastest way to upset a barbecue or dinner-party host was to inform his guests that the foundations of our prosperous country are soaked through with the blood of its original owners.

The last book I read on the subject is one I would not quite finish. Bruce Elder’s Blood on the Wattle chronicles the known history of Aboriginal murders, massacres and mistreatment so vividly, so relentlessly, that the book has earned a reputation for thrusting its readers into the depths of despair. And I was no exception! As I lay in the bath one evening, working through page after harrowing page, I came to a graphic passage in which a whooping colonial vigilante on horseback swings an hysterical Aboriginal toddler about by the legs like a polo mattock before finally dashing his head on a gum tree as he gallops by. I lay in the bath, listening to my own children playing only metres away, and in my imagination they became that little boy. As I listened to their soft voices, my fingers seemed to reach out and touch the smooth, dimpled trunk of the spotted gum in all its hardness. My wife, humming to herself in the kitchen, became the child’s screaming mother, dragged by the hair by another grinning, wild-eyed horseman, her le

gs and buttocks smashed and torn across rocks and brush, her mind snapped by the sight of her child’s crimson life-force exploding across the hardwood and into the bluest of southern skies. And as the horseman rode away to finish his work, to silence the screaming, I noticed a glinting arc of steel in his hand, and I imagined – almost believed for a moment – that it was the rusty trooper’s sabre hanging on my friend Pete’s wall.

I lay in the bath, unable to move. The water seemed to have turned red, mirroring the colours of waterholes into which entire communities were driven and cut down by gunfire amid the reeds. Stella came to the door, annoyed that I hadn’t answered her repeated calls that dinner was about to be dished up. She looked down at me and in her face I saw my own terror reflected. She snatched the hardbound book from my hands and in a tone that both pleaded and demanded, said, ‘Enough!’

I managed to conceal the true depth of my despair until a few days into the New Year. Each morning I awoke feeling as though I had been buried up to my neck in wet sand on a deserted grey beach. The Wamba Wamba were long gone. Just behind the desolate sand dunes the world rolled on like a funfair in all its boisterous beauty, and no matter how much I opened my senses to feel it, it remained untouchable. As the days progressed a smothering tide crawled towards me, around me, over me. I mouthed silent bubbles at a dazzling sky bouncing through the swirling lens of seawater. I looked down and saw my own drowning.

Suicidal feelings wormed their way into my otherwise blessed life. I had a loving wife and two button-cute little girls with endless reserves of love – yet every time I passed through my garage a coil of rope called to me. A couple of times I even walked over to it, stroked the coarse synthetic fibres and imagined its unyielding bite around the soft flesh of my neck. Mercifully, I always found enough strength to put it away, out of sight. But I knew where it was, patiently waiting until the day came when my legs would surely conspire against my soul and carry me down to its hiding place, out into the back yard beneath the sturdy bough of our jacaranda tree.

‘Stella, I’m in trouble, I don’t trust my legs any more, I think they are going to kill me,’ I cried, breaking down one morning after the children had been packed off for the day. I told my shocked partner of 20 years about the torrent of suicidal feelings that had all but swept me away from my lifelines of love and rational thought. ‘I need help, today!’

Somehow just talking about it eased the pressure enough for us to formulate a plan. We were financially stretched but I knew that the University had a free student health service which offered counselling. Minutes later I had a priority appointment.

The student services counsellor might as well have been an angel of deliverance. After the first visit I felt as though I could breathe again and by the second the awful death-tide had receded. Nevertheless, it was still out there, ready to rush in again should my mental weather darken. I was referred to a psychiatrist, who after a 40-minute consultation wisely pronounced that I was a ‘rapid-cycle bipolar’ but that with proper medication all would be well. I grasped at his diagnosis, relieved that my mental desperation had a name and was curable.

‘I’ll do whatever you recommend,’ I agreed, almost kissing his Italian leather sneakers in gratitude.

For the next six months I visited the psychiatrist’s reclining chair once a fortnight.

Since my first visits to the University counsellor, which involved just talking and gaining an under– standing of depression, I’d certainly begun to feel better; but the drugs my new doctor prescribed were an entirely new version of hell. I’d managed to avoid the rope and its sudden final jerk, but the little pills I agreed to swallow each morning and night drained my life away in a different manner. Within weeks I was a pale, drooling shell of my former self. Friends were shocked at my appearance and phoned Stella to express their concern. My hands began to shake, making it difficult to do up even a shirt button. I found it difficult to balance on my bicycle, let alone find the energy to pump up the tyres. Whereas once I could write hundreds of words a day, now I was barely capable of finishing a sentence. My marks at university began to slide and I requested extension after extension on assignments. I slept for hours each day. In desperation Stella phoned the psychiatrist and pleaded with him, ‘Yes, John was depressed, but he was never this bad, he was never like this!’ The psychiatrist was incensed that my wife – a woman who has known me for over half my life – should question his judgement.

‘Your husband’s problem is that he is fighting the medication, he won’t surrender to it, he won’t comply!’ he screamed down the phone. ‘If I had my way I’d admit him to our private hospital for a month, that way we’d get him sorted out once and for all!’ Stella was dumbfounded. ‘I think he’s the crazy one,’ she sobbed into my shoulder.

After a few more weeks the doctor grudgingly conceded that the medication was having adverse effects and instead prescribed lithium, a once-common treatment for schizophrenia. Lithium, a toxic chemical used in batteries, is a high-risk medication that requires weekly tests to monitor its levels in the bloodstream. Now I had two heavy mood-altering drugs coursing through my body. As the blood was drained from my arm each week, the bills from my psychiatrist and weekly pathologist tests steadily drained our bank account. One day I noticed that I was no longer walking but shuffling, like the character Randall Patrick McMurphy in One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest – after the operation. And it was then I realised that the same fate was befalling me, except mine was a chemical lobotomy. Despite every last hair on my body being sedated, despite wanting to fall into a thousand-year nap, something inside me began to fight back. I realised that there was nothing inherently wrong with my mind; I was merely an artist who had bombarded his sensitive spirit with the ugly truth. I seized hold of that belief; it became my mantra, my lifeline. And as I pulled that belief closer, hand over shaking hand, I came to understand the power of the artist’s way of seeing, of feeling.

I sat in the psychiatrist’s waiting room leafing through the pages of his Saab Owners Club and Epicurean magazines and realised that this man was merely a foot soldier for the transnational drug corporations. His methodology had little to do with individual wellbeing, growth or joy – it was all about compliance; shuffling happily into line in this ‘brave new world’. I began to run Google searches on the medications I was swallowing, and while the treatments are undoubtedly beneficial to some people, a paper mountain of dissenting opinion and contrary evidence began to accumulate in my printer tray. Drugs like the ones I was being told I would be dependent upon for a lifetime were an extraordinarily lazy and mind-bogglingly profitable solution to some of the fundamental problems which challenge the human condition.

As I commenced my four-week teacher training practice this realisation became blindingly obvious. I was placed in a local state school which had a higher-than-average proportion of children with behavioural problems: Asperger’s syndrome, autism, attention-deficit disorders. I spent many hours in my first two weeks coaxing students out of trees and back into the classroom, or if need be into the special ‘quiet room’. I read with interest the medical noticeboards in the staffroom outlining the various behavioural quirks, allergies, drug schedules and ‘what to do in an emergency’ details of each student. I observed the chemically laden, over-refined packaged foods the students pulled from their lunchboxes and bought at the tuckshop. I watched as harried parents disgorged their already stressed offspring at the school gate from hulking SUVs and thought to myself, ‘Is it any wonder?’

One afternoon as I wobbled home on my bike, I emerged from a quiet, creek-side bike track near the confluence of three major roads. The contrast between the tranquillity of the remnant bush and the rivers of peak-hour cars was astonishing. I sat on a low fence and watched ten thousand defeated faces slip by; expressionless, boxed in behind tinted glass. Overhead a billboard promised happiness in a wineglass, another mateship in a beer bottle. Further along, another promised longer and more satisfying sex. On the rear of a tru

ck I saw a bumper sticker I’d seen hundreds of times before, but for the first time understood its threatening undertone: ‘Australia. If you don’t like it, leave!’ I wondered, is this how Mary felt when he peered from the Barmah Forest into the margins of the new world? As I looked out at all that metal and rubber ceaselessly rushing by, everything seemed at odds with what it means to be human. And I wondered, is this what my madness means – to be able to see through the illusion, to feel things as they really are?

The next day I wandered down the hallway which led to my classroom. A young teacher was pinning up paintings along pieces of cord in front of the louvred windows. She explained that they were portraits of famous Australia explorers – Blaxland, Cunningham, Stuart, Leichhardt, all the usual suspects. Many of the artworks had a Picasso-esque quality about them and I told her I liked them very much.

‘Yes, we studied Picasso in our art unit as part of our study into portraiture,’ she said proudly, ‘so I took the opportunity to blend elements from the art unit with our Australian history unit.’

We talked a little more about art before I added, ‘Did you know that many of these explorers had Aboriginal guides and did little more than follow the walking trails and trading routes that existed for centuries? So in some ways these men didn’t actually discover anything at all.’ My voice swelled with an enthusiasm that I had barely known in months. ‘I could bring you in some material, and by the way, have the children seen the Horton’s tribal map of Australia yet? It is astonishingly beautiful and will change the way they think about their country forever. I really think it should be displayed prominently in every school in Australia.’

Riding the Black Cockatoo

Riding the Black Cockatoo