- Home

- John Danalis

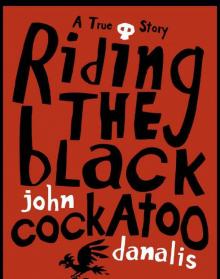

Riding the Black Cockatoo Page 14

Riding the Black Cockatoo Read online

Page 14

She looked at me a little strangely; perhaps she was alarmed by the excited spittle that flew off my words.

‘Well, we aren’t covering any Indigenous units this year, so that wouldn’t really be appropriate.’

And with that she went back to pinning up a cubist Burke and Wills.

In a strange way the paintings became a turning point for me. Each time I passed those 30 bizarre portraits, a breeze would gently billow them out into the hallway as if they were breathing. It was truly unsettling, and more than once I had to close my eyes to regain my composure. It also hammered home the limitations of the current education system; these children were being taught many of the same tired old lessons I had been taught over 30 years ago. I resolved then and there never to teach from a curriculum; if I was to work with children I would teach from the heart. A week later I formally withdrew from prac and at the end of that semester from the teaching degree altogether. Resolving to free myself of the terrible chemicals that were poisoning my spirit, I found a sympathetic doctor who helped me formulate an escape plan and would monitor my withdrawal. But to get well again – to be truly healed – I knew I would have to visit Mary.

CHAPTER

SIXTEEN

{ MELBOURNE, 16 april 2006 }

I floated over the Victorian border at 15 000 feet in the late afternoon with my nose pressed to the little window and there it was, the Murray River shimmering below. It looked just as it is described in the creation story; those big bends carved into the land by the giant Murray cod Kurrumeruk's thrashing tail as rainbow serpent Yemurraki pursued him from the mountains, across the horizon to the sea. From this height the river looked as if it had been created yesterday; each bend caught mercurial flashes of late-afternoon sun and belted them heavenwards again, reminding me of one of the river’s Aboriginal names, Millewa (stars on the water).

The land rolled away in a tapestry of patchwork properties stitched together with barbed-wire fences and bitumen. Occasionally a tiny tuft of remnant forest broke the monotony, but these lonely pieces were few and far between. No wonder the original owners were squeezed out so rapidly, so effectively. I scanned the river, hoping to recognise the settlement of Swan Hill – for only a few kilometres upstream, on the northern bank, Mary lay in Wamba Wamba soil.

I’d arranged to stay with friends in Melbourne. Craig picked me up from the airport. We hadn’t seen each other for over a year, but our conversation came easily in the way it does between good friends. I didn’t tell him how ill I’d been or that I’d been living in a drug-induced nightmare. Somehow just seeing the river, being closer to Mary made me feel steadier. When my friends showed me to their spare room, I stopped in the doorway. Over my bed hung a poster; a reproduction of Craig Ruddy’s Archibald Prize-winning portrait of David Gulpilil. The painting, entitled Two Worlds, is an extraordinary work that crackles with an otherworldly intensity and energy. I lay on my bed and smiled as this colossus of Australian cinema and Indigenous culture stared across the room. I was getting closer.

{ 17 APRIL 2006 }

The next morning I phoned Gary. He knew I was coming and had promised to take me to the property, but he seemed far from happy to hear from me. He said something quickly about being in negotiations with the Victorian state government to save the ‘sacred flame’. Gary suggested I call again later in the day, and hung up. No ‘Welcome to Koori Country’, not even a hello; what a disappointment! I suppose I was expecting to be greeted with wide open arms. I sat on the end of the bed for a while, staring up at David Gulpilil. In that portrait the lines in his face are rendered like stringybark; his dark eyes look towards a horizon. He seems to be waiting for something he knows is coming, but in his eyes there is anxiety, as if he is worried that he won’t quite live to see its arrival. Perhaps I was reading things into those eyes, but they helped put things into perspective. My story was but a footnote in an epic saga. Mary’s remains were but one amid tens of thousands still waiting to be returned. And my troubled spirit was infinitesimal compared to the real struggle that affects Indigenous Australians day after day after day. Mary might have been laid to rest but the reconciling of unfinished business continues.

My hosts had left a newspaper on the breakfast table for me and as I chewed my breakfast I scanned its pages with half interest. A headline containing the words ‘sacred flame’ leapt out at me. No wonder Gary sounded so preoccupied. The ‘sacred flame’ was a ceremonial fire which burned on Melbourne’s Domain, a hilltop corner in parklands only a short distance from the war memorial, the Shrine of Remembrance. The fire had been lit as an ‘alternative remembrance’ of Indigenous peoples and a protest camp had grown around it to shelter the keepers of the fire, and to provide comfort to those who visited it each day. Gary was fighting to overturn a court eviction notice ordering that Camp Sovereignty be dismantled.

It was a two-hour walk from my friend’s house in the north of Melbourne to the Domain parklands just south of the Yarra River. As my legs carried me towards the fire, it was impossible not to be impressed by the results of 150 years of European endeavour. Melbourne is such an elegant and visually generous city; you can feel the love that has gone into her stonework, latticing and landscaping. Caught up in the bustling beauty of the city, with its tree-lined streets and fine architecture paid for with golden nuggets, it is easy to forget its original occupants.

Crossing the Yarra, I entered the parklands, searching the treeline for tell-tale smoke. Remembering the wonderfully scented lemon myrtle from my own back yard, I looked about for a fallen branch; something I could place on the fire as an offering. But as I scanned the manicured gardens, I realised that none of the trees about me were native; they all appeared to be introduced species: elms, oaks and willows. In fact the entire design of the parklands reminded me of the great public parks of London; it looked nothing like Australia. And then it dawned on me: who was I to lay a branch on the sacred fire anyway!

My nostrils found the ‘sacred flame’ for me. Unlike the odourless, gas-lit flame at the official Shrine of Remembrance, this flame was fed on native logs and branches which were hauled in especially. White smoke wafted about the camp, its native scents at odds with the deep green weeping foliage of the surrounding trees and the glinting office-tower backdrop of the central business district. A couple of red, black and yellow banners roughly marked out the perimeter of the camp. In my readings I’d learnt that it was traditional etiquette never to walk into a camp uninvited; one had to sit at its margins in full view of the clan, sometimes for days, before the elders felt the visitor was trustworthy and free from bad spirits. At Camp Sovereignty, a hand-painted sign politely asked visitors to do the same. I waited, a little nervously. Before all this business with Mary, I would never have dreamt of wandering into any sort of protest site, let alone an Indigenous one. Before long, two young white women joined me; they were office workers and had popped over in their lunchbreak to learn more about the fire. Soon others came: another young woman from the local art college and an impeccably dressed antique dealer in his fifties. After about ten minutes, two Koori women approached us with wide smiles. They led us into the camp, explaining that visitors were not permitted to go near the fire unless escorted. The sacred fire was set within another clearing, the perimeter of which was marked out with foot-long upright logs. ‘There’ll be a smoking ceremony a bit later, so we’ll all get the chance to breathe in that good healing smoke,’ one of the women explained. ‘Come and get yourselves a hot cuppa, there’s plenty of bikkies too.’ A couple of folding tables were set up with provisions and a gas camp stove brought a billycan of water to the boil.

There were about a dozen Kooris at the camp and everyone made us welcome except one man whose face seemed perpetually contorted by anger.

‘Why do these white bastards keep showing up,’ he ranted to no one in particular, ‘this fire is none of their fucking business!’

‘Oh don’t mind him,’ said one of the other women. ‘He’s been here since t

he fire was started and he hasn’t had much sleep for the last month. It’s hard work watching the fire all through the night, especially in the rain. It gets windy up here too.’

The women explained that the hill we stood upon was a traditional meeting place called Mumajah, a neutral space where clans had come together for centuries.

‘Big corroborees were held right here,’ she said, as a breeze slowly billowed the Aboriginal flags on their makeshift bamboo poles. ‘Business was conducted here too, disputes between different mobs worked out; still is. Every few days the lawyers come, the Lord Mayor has visited too. And just over there,’ she said, motioning with an outstretched hand but with eyes averted from the place she was pointing to, ‘lie thirty-eight of our people, returned after a long battle with the Museum. There’s also generations of ancestors buried all around us.’

A little later a bearded Koori approached us. He appeared to be in his fifties or sixties – but as with Auntie Alyson, it was impossible to tell. He wore loose clothing of earthy weaves; beads, stones and feathers hung from him with transcendental potency. A green, yellow and red cap – the Rastafarian tricolour – topped off his ensemble. He smelt of the smoke; he was the smoke. I had met my first Wirinun – an Aboriginal shaman.

The Wirinun formed us, black and white, into a line and brushed us over one by one with the smoking branch of a green eucalypt sapling. Despite the smoke, the leaves felt cool, their oily freshness resisting total ignition. He explained the importance of fire and how it lay at the root of Aboriginal Law and culture. ‘Fire is our gateway to the Dreamtime. This smoke is a healer; come, breathe it.’

The fire had been primed with fresh green branches. As it billowed with white aromatic smoke we were led slowly around it. Some of us wept cool tears, some of us simply smiled; we breathed deeply and allowed the smoke to penetrate our personal cuts and private wounds. Memories of Mary’s handover came flooding back; I thought of my family, my parents, the elders with eyes full of forgiveness, and cool tears streamed down my cheeks. Gone was the psychiatrist’s couch, gone were the ‘If You Don’t Like It, Leave’ bumper stickers. As I drew the smoke into my being I felt a peace rise through the soles of my feet. Our procession snaked its way around the ‘sacred flame’ in a continuous circle, and all of us – black, white, country, city, rich and poor – became one.

{ 18 APRIL 2006 }

The first thing I saw when I opened my eyes the next morning was that portrait of David Gulpilil. Even on paper he dominated the room. I stretched out, feeling fresher and more alive than I had since those dark days over Christmas and New Year. I had tried phoning Gary a few times the previous evening and each time the phone rang out. I wasn’t too concerned; I was getting used to things unfolding naturally and in their own time. I knew we’d meet soon enough. After breakfast I phoned Jason, who boomed down the line, ‘Hey! Welcome to Melbourne, my brother.’

I told him I was having trouble making contact with Gary. ‘Phone me this afternoon, I’ll sort everything out,’ he promised. I headed into the city again; it was a long walk but the walking seemed to make me feel strong again, as if I was purging my system of all those life-robbing chemicals.

I arrived at the information desk of the Melbourne Museum and asked if Simon from the Indigenous Collection was in. Minutes later we were shaking hands. Simon led me to the Museum cafeteria. Over coffee, I told him all about Mary’s return and of the positive effect that it had had on my family. He smiled as I recounted the driving incidents and laughter I’d shared with Bob and Jason.

‘You were lucky with Mary,’ he said. ‘In the vast majority of cases we have no idea where the remains have come from. But we can’t just hand them all over the way some clans want us to, that would be irresponsible; the Museum would have to answer to future generations if we did that.’

He went on, ‘You know, Jason really burnt some bridges here, the museum had no choice but to let him go.’

‘Well, I can understand his point of view,’ I replied. ‘He literally tripped over the remains of his ancestors, didn’t he?’

Anger flashed across Simon’s face before softening into sadness. ‘The trouble with the clans is, they think they’re the only ones allowed to feel. I’m up there in those storerooms day after day, is it so hard to imagine that I might speak to them too? When we’re alone, I talk to them.’ He looked away.

I told Simon that once enough water had passed under the bridge, that once I was strong enough, I might write a book about Mary’s return to country. One story to speak for all the bones still in drawers and about the people on both sides of the fence who cared deeply about them. Simon looked at me intensely. ‘I can’t believe anyone would be interested in what I do up there, about the way I feel.’

‘I reckon they would,’ I answered. ‘It’s your side of the story that makes it complete.’

A friend of mine once commented that one of the stumbling blocks to Reconciliation in Australia is that too many people believe that all blackfellas are mystical and that all whitefellas are mean. And as Simon organised a special visitor’s pass for me I understood fully what my friend had meant. ‘Make sure you check out Bunjilaka,’ he said, pointing me in the direction of the Museum’s Indigenous collection. ‘We’re really proud of the work we’ve done there.’ As he walked away he turned and called, ‘And say hello to Mary for me!’

At the northern end of the museum, past the Cobb & Co Coaches and other pioneer displays, lay the entrance to Bunjilaka. As I entered the first section my heart literally jumped for joy. I’d walked straight into an extensive exhibit on possum-skin cloaks. All around me were stunning reproductions and new designs, the ancient tools of the craft as well as the new ones. I watched a video display featuring the ladies who were reviving and reinterpreting the craft. But best of all, there in a softly lit glass case was the Lake Condah cloak, one of only six nineteenth-century cloaks in existence (of which four are held in overseas collections).

After an hour I wandered into the next exhibit, which featured a display on Aboriginal burials and the importance of a final return to country. Central to the exhibit was a long black Chrysler hearse featuring Aboriginal flags on the front doors. The hearse was purchased in 1976 by the Aboriginal Advancement League and made available for the return of Indigenous people to their own country for burial. I felt a strange connection to the hearse, and peering into its windows tried to imagine the drivers and their assistants who sat upon the broad bench seats as the wagon traversed the highways and dusty back roads of Victoria.

After spending half the day in the museum I headed for the exit, overloaded with new insights and understandings. A flash of red and black caught my eye. The museum gift shop had a display of cuddly toy birds in the window, and sitting among the many species displayed was my old friend, the Red-tailed Black Cockatoo. I purchased two birds for my daughters and as the sales assistant put them in my shopping bag she gave each of the cockatoos’ tummies a playful squeeze, setting off the little soundbox inside. ‘Karak! Karak!’

My legs took me south again, towards the Domain parklands and the ‘sacred flame’. But the mood there was different this time. A television crew from one of the commercial stations’ current affairs shows had set up on the perimeter. The male reporter, a large oaf in an expensive-looking suit, was goading a couple of the young male firekeepers. The cameras were poised to start rolling the instant there was action. Meanwhile the sound man was swinging his long microphone boom through the air over the heads of the frustrated protesters.

‘Oh sorry, are we violating your sacred airspace?’ jeered the reporter.

Another reporter, a young dolly-girl in a tight mini dress, giggled and cooed at her male colleague. Eventually one of the young Koori men broke ranks and crossed the perimeter. He stood inches from the reporter’s mocking face and half pleaded, half demanded, that the crew leave them in peace.

‘You fellas have no idea what this place means to us, you have no idea how much pain you are causi

ng us.’

The reporter had been waiting for this; he motioned to a ring of empty beercans that one of the technicians had fished from a nearby rubbish bin and arranged in a rough circle around the crew.

‘Listen, you little black cunt,’ he snarled, ‘can’t you see you’re intruding on my sacred ground.’

The crew, especially the female reporter, fell about laughing. A cameraman thrust his camera in the young Koori’s face, waiting for him to snap. Summoning up a super-human level of self-restraint the young man turned his back on the reporter and walked slowly back into camp.

‘You gutless little black shit!’ the reporter called, clearly frustrated that he’d been denied some sensational footage. ‘I’ll be waiting for you.’

But despite the heavy mood, the supporters kept coming: a couple of young surfers, a dreadlocked hippy, two German tourists. I introduced myself to a local Koori girl who turned out to be a reporter for the local Indigenous radio station. When she heard of the reason for my visit, she whisked me to a quiet spot under a tree and with one hand holding a microphone and another wiping away tears, recorded my story of Mary’s return. But there would be no smoking ceremony that afternoon, not as long as the media jackals prowled the perimeter.

As the sun set I headed north again, stopping at a phone box to touch base again with Jason.

‘Hey, John! It’s all set, we’ll meet you at the pub in Nicholson Street at seven tonight, it’s directly across the road from the Melbourne Museum.’

I set the alarm and collapsed into my bed for a two-hour nap. All that walking, all that emotion had gotten on top of me. I felt as though I’d packed a week into one day – and it still wasn’t over! My friend dropped me at the pub just before seven; it was a nice place, tastefully decorated and softly lit. Jason arrived soon after and welcomed me with his beautiful big smile and a bear-hug. He was working for the Melbourne Comedy Festival, which was in full swing, and was still heavily involved with all his cultural obligations. Here was a man operating in two worlds; he looked tired.

Riding the Black Cockatoo

Riding the Black Cockatoo